Wouldn't this advice be helpful every Friday?

Sign up to receive Tom Brown's Exclusive Banking Weekly in your Inbox each Friday.

Copyright 2018, Second Curve Capital, LLC. Copyright notice: It is a violation of federal law to reproduce this newsletter in any way, including via photocopying and email forwarding. The Copyright Act imposes liability of up to $150,000 per issue for infringement.

Printed by:

–Copyrighted Material; Do Not Forward, Photocopy, or Redistribute In Any Way–

Vol. VII, No. 8

TOM BROWN’S BANKING WEEKLY: 3/4/22

Financial Services Insights and Intelligence

FIRST WORD: My conversation with Wells Fargo CEO Charlie Scharf. I first met Charlie Scharf in 2000 when Jamie Dimon brought him in to be the CFO of Bank One shortly after Dimon became CEO. Scharf and Dimon started working together in the 1980s as part of Sandy Weill’s team that turned the old Commercial Credit into Salomon Smith Barney, which ultimately became Citigroup. You can understand that two individuals who worked that closely, and for such a long time together, must share key management philosophies, and they do. So when Wells announced in October, 2019 that Scharf would be its new CEO, I told everyone that asked that there was no question that Scharf would turn the company around and in all likelihood turn it into an industry leader again. Just watch, I said.

Honestly, the turnaround has taken much longer than I expected, as the company is still operating under a consent decree and an asset cap. In addition, there has been much more turnover among the company’s senior management than I expected. Eleven of the 18 members of the operating committee are new to the bank since Scharf’s arrival, and two of the others are in different positions. In addition, over half of the 200 people in the management layer just below the operating committee are new to the bank. To find out why the turnaround is taking so long and why there have been so many management changes, I spent some Zoom time with Scharf this week.

My perspective on the problems. There are no two companies I’ve spent more time with over my career than Norwest and Wells Fargo. Norwest became a great company under Dick Kovacevich. He formed a company that consisted of an urban commercial bank, a community bank, and a collection of non-bank subsidiaries. Wells Fargo became a great banking company under Carl Reichardt and Paul Hazen, but stumbled badly after Reichardt retired and Hazen acquired First Interstate. After Norwest bought Wells Fargo and kept the Wells Fargo name, Kovacevich led the company back to greatness, but the combination diminished the importance of the commercial part of the community bank, and it began a slow decline as a part of the company.

Kovacevich’s management style was to let strong managers run what became 80 or so businesses. The emphasis was on running your business and trying to cross-sell the products of the other units to your customers when possible. This decentralized management structure worked because Kovacevich understood all the businesses and would hold the managers accountable. It worked until it didn’t. The recession of 2008 really marks the beginning of Wells Fargo’s downfall, in my opinion.

First, because of the company’s financial strength, it was able to make a financially attractive acquisition of Wachovia. However, the acquisition significantly increased both the asset size of the company and its complexity, the latter of which would become a problem. The recession also brought Dodd-Frank and, with it, new regulations and a new regulatory approach. The other large banks adjusted or were forced to adjust by their regulators, but Wells did not because the company’s strength in the recession just seemed to show that it had the right management and processes.

While Wells had strong credit-risk management, its decentralized management structure was not supplemented by an overarching compliance process. This enabled a rogue manager, Carrie Tolstadt, who ran retail banking, to take a good concept, cross-selling, and turn it into a dangerous practice by incenting employees to hit ever-rising sales goals or be fired. Fake accounts were created. One example of the bad behavior: in Arizona, Wells Fargo branch employees would travel to nursing homes to offer no-annual-fee credit cards to residents. The cards weren’t used, so the only economic impact was that the bank paid an unnecessary incentive to an employee. There were other schemes, and this went on for years. Individuals would be fired, but there was no fundamental change in the sales approach. There was no strong compliance process that would prevent bad sales practices from continuing, until the media and Congress got involved.

Congress’ ire at Wells Fargo and its senior management was one of the few bipartisan issues that has occurred in the last decade. This of course was a huge embarrassment to the regulators, who came down hard on Wells Fargo and its management. Three different CEOs tried to fix the problem with Tim Sloan and Allen Parker making some progress, but the company needed a complete overhaul in its management.

I am not sure the board knew that the decentralized management structure, which worked so well under Kovacevich, needed to be changed, but he was no longer there and the bank was different in a post-Dodd-Frank environment. The board couldn’t have found a better person than Scharf to install a new management system.

Scharf spent the first few months assessing the situation and his team. He says now that the problems were bigger than he realized when he took the job. He methodically kicked some people off the management bus that he didn’t think were best for the new management style and he hired people from the outside to fill these key roles.

Changing how the operating committee works. When Scharf started, he had two meetings of the operating committee every day. The old style at Wells was to not ask questions about someone else’s business at such meetings. Scharf had to change that to get the discussion he wanted. He says it didn’t happen naturally, but with time, it has. Eventually the operating committee meetings went to once a day, and now they are twice a week, with one full-day meeting per month when they go through the budget. Each manager is responsible for his own business and is expected to ask probing questions of the others. Scharf is very happy with his team and how they are operating now, particularly with respect to accountability.

Lowering the expense structure. One of the first things Scharf did was look at the business-line structure, make some changes, and then ask for an analysis of how each unit’s profitability matched up against the best-in-class. He concluded that the company’s expense structure in virtually every business line was too high. He then set out to understand how each business operated so he could make intelligent expense-reduction decisions. He said he learned to know the details of the plumbing from Jamie Dimon at Commercial Credit. He also said Dimon learned its importance from Sandy Weill, who was running a brokerage firm when stock trading commissions were deregulated. To survive after commissions subsequently fell, brokerage firms needed to understand their costs, which they hadn’t needed to in a fixed-commission environment. I am confident that one of Scharf’s legacies from his tenure as CEO will be how he changed how the senior managers at the company think about expense management.

Why are so many commercial bankers leaving? I told Scharf that almost every CEO I’ve talked to at banks with between $1 billion to $100 billion in assets has crowed about the lenders they have hired from Wells Fargo. It was news to him. I was stumped by his response because I haven’t been told that Wells Fargo is the “gift that keeps on giving” just once or twice, but rather 30 or 40 times over the past two years. We moved on, but after the call I realized why we had such different perspectives. The lower-middle-market commercial banking part of community banking has shrunk so much at Wells that it is irrelevant to the company’s earnings today—which is surely one reason why so many of the company’s experienced bankers are leaving.

Why are retail customer satisfaction scores so low? Long before the phony-account scandal, Wells Fargo’s retail customer satisfaction scores have been surprisingly low, and they have gone lower over the last few years. There are many different measures such as Gallup and J.D. Power, but Wells has always been below average. The latest J.D. Power survey of the largest U.S. banks ranks Wells dead last. Scharf said he thinks there are a couple reasons for the low scores. First, there’s the hangover from all the negative media publicity the company has received. Second, the company hasn’t been marketing because of the asset cap. In addition, to avoid any appearance of overly aggressive sales practices, the company has been doing some “unnatural things.” I expect Wells’ customer satisfaction scores to rise with its marketing spend, after the asset cap is lifted.

Is Wells Fargo at a branch network disadvantage? The banking industry went on a bank-branch-building spree from 1998 to 2009, resulting in about 100,000 branches in the U.S. Since then, branches have declined at an accelerating pace and there are now around 80,000. Bank of America was the smartest among the large banks. It recognized that its retail banking model was urban-centric, so it sold or closed many of its rural branches. JPMorgan Chase never had many rural branches, nor did Citi, but Wells Fargo does, and it was late to the branch-network reduction game. In light of growing political pressure to not close bank branches, I asked Scharf if Wells Fargo will be left with more branches in areas they don’t want than the others. He is aware of the issue and says Wells is very careful to not close a branch that would leave a community bankless. In addition, he said Wells can shrink staff and hours such that it won’t be an issue.

How damaging is the asset cap? As part of its regulatory agreement, Wells Fargo’s assets are limited to the level they were at the time of the signing of the agreement. There is no question that this has forced the company to go through some gymnastics to stay in compliance. As Scharf told me, “There is no remedy if we go over the cap. We don’t know what the penalty would be, but we’re pretty sure it would be severe and we don’t want to find out.” When the pandemic hit, large corporate borrowers drew down their unused lines of credit, causing explosive growth in loans and deposits. Then consumer deposits spiked from stimulus checks. To stay below the cap, Wells had to push non-relationship corporate deposits out of the bank. The level of deposits is what Wells has to manage hardest to avoid going above the cap. Scharf says the company still has plenty of capacity to make loans. The lifting of the cap will be a bigger deal than I previously thought. It will be a huge boost to morale internally and it will enable the unleashing of Wells’ retail marketing engine. With the company’s balance sheet growing, earnings growth prospects will brighten.

Why has the fix taken so long? Despite all the experience I’ve had watching banks try to work out from consent orders, I continue to be surprised at how long it’s taken Wells Fargo get out from under its regulatory cloud. The fix is now on its fourth CEO. Scharf reminded me that the groundwork for consent orders usually starts well before the actual order, with oral and written requests to change practices, so if a consent order is actually required, the regulators must be very upset, and more so given all the publicity in this case. After the consent order, the company had to develop a comprehensive plan, have it approved by the regulators, then implement and monitor the changes. It then will present the findings to the regulators, and then the regulators need to certify the changes. “It just takes time,” Scharf said.

Charlie Scharf has always been the right person for the job both the fixing and the growing part. It is a new company, with a new management team and a new method of operation. That will be rewarding for shareholders eventually, but the new company will only have a few vestiges of the community-bank part of the old Norwest. The U.S. will end up with three great national banking companies and a thriving community banking industry. The community bank king inside Wells Fargo is dead, long live the king!

THE SURGE IN NEW BUSINESSES: There were 5.4 million applications to start new companies last year, a 53% increase from the pre-pandemic level of 2019. One-third of those applications were classified as “high propensity” applications, indicating that the businesses are likely to create jobs for others. The pandemic gave people more time and resources to contemplate their work future. The working from home environment could have also fostered more gig work on the side.

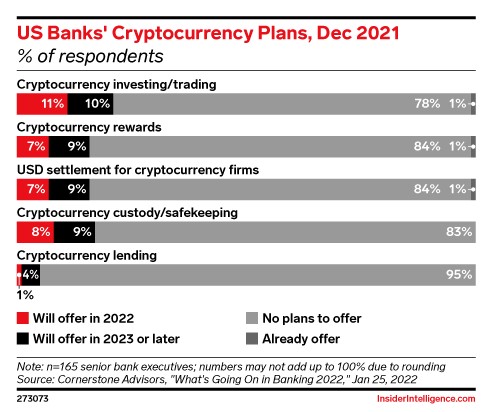

SHOCKING CRYPTO POLL: When I first saw the results of this poll, I had to double check its date, (which is current) and the source, which is reliable (Cornerstone Advisors). It’s hard to believe that only 1% of U.S. banks currently offer crypto trading and investing services to their clients, and even more surprising that 78% have no plans to do so.

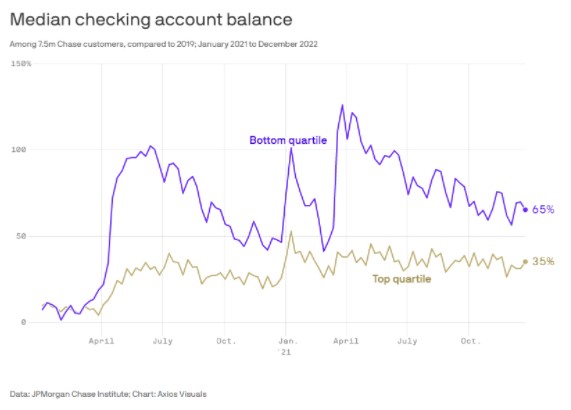

SAVINGS STILL BOOSTED: A change in consumer behavior and government benefit programs, both responses to the pandemic, boosted the savings levels of both low-earning individuals and high-earners. It’s encouraging to see that the savings levels of both remain elevated, especially that the savings level of the low earners is 65% above pre-pandemic levels, admittedly off a small base.

WOBBLY: Such unswerving vigilance! Jerome Powell, on Wednesday:

I am inclined to propose and support a 25 basis-point rate hike. To the extent that inflation comes in higher or is more persistently high than that, then we would be prepared to move more aggressively by raising the federal funds rate by more than 25 basis points at a meeting or meetings. [Emphasis added.]

Do you think this is the sort of approach a central banker determined to quickly get inflation under control would take? I don’t. Where the heck are the bond vigilantes when you need them?

CITI AND KEY PRESENT TURNAROUND STORIES: WHO TO BELIEVE?: Both Citigroup and KeyCorp have very long track records of making big promises and following up with disappointing results. Citi invented the “investor day” concept in the early 1980s with a flashy annual presentation it held every year in an auditorium at its old headquarters on Park Avenue. One year it would focus on the commercial bank and the next the retail bank. The presentations were awe-inspiring particularly to a relatively young analyst like me, but the company never came close to achieving its projections, and eventually gave up investor days.

Key’s history of disappointment is shorter but still long from any perspective. KeyCorp lost its way in 1993 when the then-Buffalo-based company announced a merger of equals with Society Corp., based in Cleveland. KeyCorp’s geographic footprint went across the northern part of the U.S., from Maine to Alaska, as a result of the reckless growth strategy of CEO Victor Riley. Society had spent the previous decade raising its profitability to above-average levels, and made a financially attractive acquisition of Ameritrust, also In Cleveland, in 1991. The Key-Society combination was one of the many merger-of-equals disasters. Bob Gillespie ran the company after Riley, and was succeeded by Henry Meyer, who presided over major credit problems in the 2008 recession. Then Beth Mooney took over from Meyer and stabilized the institution. In May, 2020, Chris Gorman was promoted from within to run the company.

In short, I’m skeptical of the new Citi strategy and the company’s ability to execute, but the stock’s valuation is so depressed it might provoke some investor enthusiasm. As for Key, I bought in to the transformation before the investor day because of changes that have already been put in place, most notably:

- The company’s loan portfolio has been de-risked. This took place under Mooney and is evident given their stress test results.

- A young, impressive management team has been assembled, full of people who appear to me to have a strong desire to work for a winner.

- Gorman has instilled a new strategy best described with three words: focused, disciplined, and differentiated.

A couple weeks ago I wrote about having two companies that I am closely watching because I think they have the pieces in place to go from good to great, and Key is one of them.

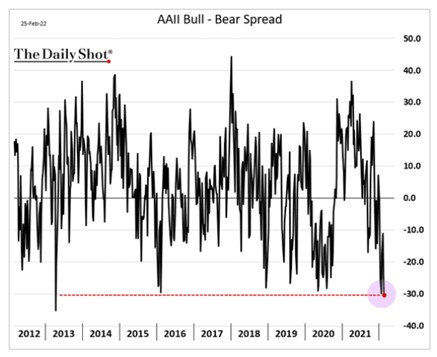

MOODS SOURING: Here’s one positive result of all the market and geopolitical tumult that’s been going on lately: investors haven’t been this pessimistic in years.

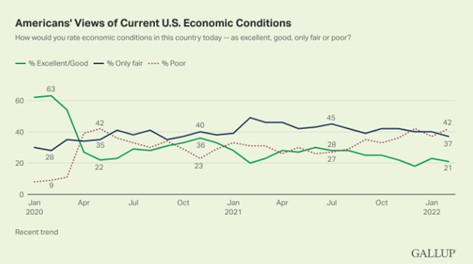

NOT SO HOPEFUL: Speaking of how people are feeling these days, the number of Americans who tell Gallup they think economic conditions in the U.S. are good is just about as low as it’s been since the pandemic began.

TECH JOBS ARE MOVING: At the start of 2019, 30% of the jobs for West Coast companies were listed outside of the region; today it’s 43%. Not surprising that Texas is the main beneficiary, Virginia second.

NOT SO FAST: Oh, come on:

The top U.S. watchdog for households, the Consumer Finance Protection Bureau, issued a warning shot on Monday to lenders and loan servicers who may be tempted to illegally repossess cars as used-vehicle prices soar.

The CFBP said an extremely hot market for used cars, due in part to supply-chain bottlenecks during the pandemic, better not lead to illegal auto-repossession practices in the nearly $1.5 trillion auto-loan market.

“With today’s high car prices, auto lenders and investors might be tempted to seize vehicles for resale in the hot used-car market,” said CFPB Director Rohit Chopra, in a statement.

“No American ever wants to wake up to see their car stolen. Auto-loan servicers need to ensure that every repossession is lawful.” [Emphasis added.]

Please. Somebody at the agency needs to get a grip. High used-car prices are boosting lenders’ recovery rates, whether the CFPB likes it or not. But the companies are in the lending business. They’re not about to morph into a bunch of auto-theft rings.

TRADING AROUND VOLATILITY: It has been a difficult start to the year for equity investors, made worse by troubling global events. An environment like this creates fear among investors, who then want to take some action or other. Warren Buffett warned about this fear in his letter to shareholders in 2005. He called it “Newton’s Fourth Law of Motion.” He wrote, “For investors as a whole, returns decrease as motion increases.” Great words to remember at a time like this.

DISCONNECTED FROM REALITY: The U.S. economy has created 6.6 million jobs over the past year, a record for any twelve-month period. Still, just 35% of people surveyed by Navigator Research say they believe the economy is shedding more than normal compared with just 19% who think it’s creating more than normal.

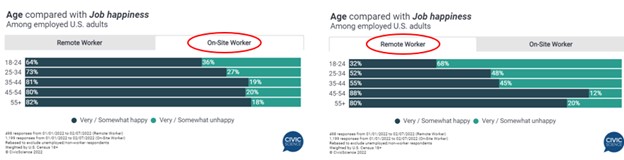

SOMEWHERE TO GO. Hang on. This doesn’t quite square with the conventional wisdom I keep hearing that widespread working from home will lead to a new worker paradise. In fact, people who work on-site seem to be happier in their jobs, on balance, than are people who work remotely.

HIGHLIGHTS FROM WARREN BUFFETT’S ANNUAL LETTER: I have long believed that shareholder letters can be the most important communication a CEO makes to stakeholders and other interested parties each year, and am surprised and disappointed in those CEOs who give their letters short shrift. The gold standard of letters is of course the ones written by Warren Buffett. His latest came out last Saturday. Some highlights.

Attitude of a long-term investor. “We own stocks based upon expectations about their long-term business performance and not because we view them as vehicles for timely market moves. That point is crucial. Charlie and I are not stock pickers; we are business pickers.”

The value of teaching and writing “. . . has taught me to develop and clarify my own thoughts. Charlie calls this phenomenon the orangutan effect. If you sit down with an orangutan and explain one of your cherished ideas, you may leave behind a puzzled primate, but will yourself exit thinking more clearly.”

Career advice. “I have urged that [university students] seek employment in (1) the field and (2) with the kind of people they would select, if they had no need for money. Economic realities, I acknowledge, may interfere with that kind of search. Even so, I urge the students never to give up the quest, for when they find that sort of job, they will no longer be ‘working’.”

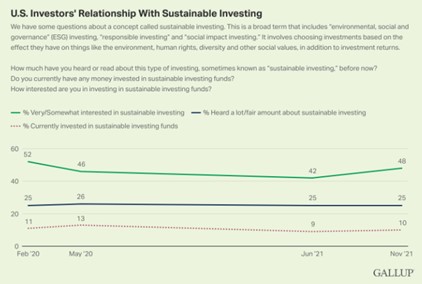

EAGER MARKET: No wonder Wall Street keeps churning out ESG-ish investment products. Nearly half of investors surveyed by Gallup say they’re interested in sustainable investing.

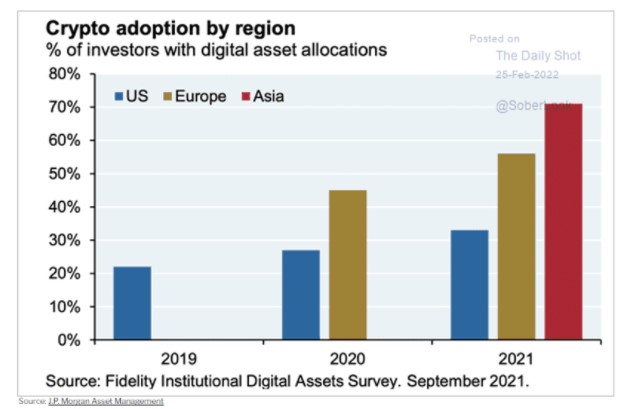

CRYPTO ADOPTION: This is a chart with only six bars, but it contains much information. I am surprised that in 2019, 20% of U.S. investors had invested in digital assets—and I’m also surprised that in the two years since, adoption in the U.S. has meaningfully trailed that of the rest of the world.

THE GREAT DIVIDE IN RETAILING: Simon Property Group, the largest mall operator in the U.S., is declaring a successful comeback for shopping malls, particularly large suburban malls. As an example, the company cites a 16% increase in foot traffic at the Scottsdale Fashion Square compared to pre-pandemic levels. However, many urban storefront retailers have not experienced such a recovery because of the persistence of work-from-home and less tourist traffic. New York City officials say that foot traffic in the city this year is running at one-fifth the pre-pandemic levels. Vornado Realty estimates that there is 90 million square feet (16 Mall of Americas) of empty store space across the U.S.

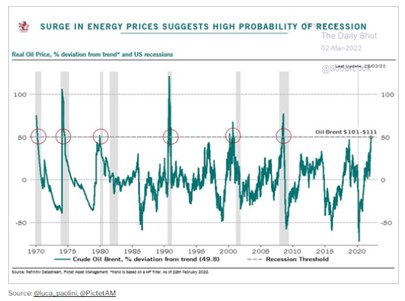

TOO FAR TOO FAST: Might rapidly rising energy prices bring about a recession? It sure seems like it, no?

CUSTOMERS BANCORP., A REMARKABLE STORY IN THREE PARTS: What was the best-performing bank stock in 2021? If you said Customers Bancorp, you’d be right. The stock has tripled during the last two calendar years. But that’s the second part of story.

To appreciate the remarkable accomplishments, go back to 2010 when Jay Sidhu made a $17 million personal investment in Century Bank, a troubled $250 million institution. Through a combination of strong internal growth and acquisitions, the company’s assets rose to $11.5 billion by the end of 2019. The company went public in 2012, and the stock increased six-fold with Jay Sidhu as CEO. That was the end of the first phase.

The next phase began at the beginning of 2020 when Jay’s son, Sam, began running the company. He had a plan for Phase Two that involved moving faster to transform Customers into a totally digitally driven company, and re-mix its asset and liabilities to lift its profitability and its stock valuation. Along the way, the pandemic hit and the PPP program was put in place. I know of no bank that handled more PPP loans relative to its size than Customers. It handled $10 billion of PPP loans. The company leaned into the program and used BaaS to support dozens of fintechs, most notably Kabbage and OnDeck. When all the PPP loans are forgiven, the company will have recorded around $350 million in loan fees. Last year it reported core earnings per share of $10.20, up 187% from 2020, with $5.79 of those 2021 earnings from PPP fees.

With the PPP program virtually complete, Customers now enters Phase Three, which is to benefit from the significant changes in how the company operates in order to improve its loan mix and funding base. There are three parts to Customers: community banking, specialty banking, and digital banking. Today the loan portfolio is one-third community banking and two-thirds specialty, and last year both parts experienced very strong loan growth. The strategy to grow both involves geographic expansion by lifting teams out of other banks.

The deposit side of the Customers transformation is off to strong start, with total deposits increasing to $16.8 billion from $8.6 billion at the end of 2019. Importantly, Customers has always had a below-average percentage of non-interest-bearing deposits in its mix, but in the last two years that has improved to 27% of total deposits.

Digital banking is the third leg of the Customers stool. The company now has over 500,000 digital-sourced customers and $1.7 billion in consumer loans. But what attracts the most attention is Customers Bank Instant Token (CBIT), which provides instant payments for cryptocurrency customers. CBIT was launched in the third quarter of last year with about 25 specially selected customers for the soft launch. By yearend, CBIT had $1.9 billion in deposits, and the company began to roll the offering out broadly. When I talked with Sam Sidhu last week, he was very pleased with the number of new customers. Sidhu was excited about all aspects of growth this year. He reiterated the company’s earnings guidance of between $4.75 and $5.00 for 2022 and well above $6.00 for 2023.

The first phase of the remarkable growth of Customers was largely driven by the playbook Jay Sidhu used when he ran Sovereign Bancorp from 1989 to 2006. Sovereign was eventually sold to Santander. The second phase was really a re-mix of the company’s assets and capitalizing on a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity provided by the PPP program. The third phase, which has now begun, involves trying to win on many fronts. The first two phases were very rewarding for shareholders, but the third one may create the most long-term value.

NEXT WEEK: On Tuesday, the National Federation of Independent Business will release its Small-Business Optimism Index for February. The consensus looks for 97.4 vs 97.1 in January. Then on Thursday, we’ll get the February Consumer Price Index. The consensus expects a month-on-month change of +0.8% vs +0.6% in January.

THE LAST WORD: Everyone knows what the term “the college experience” means. It’s a combination of the formal education students get from the courses they take and the social education outside the classroom. Most people I know would love to return to college for a refresher on the social education part. I am a boring person today and I was a boring person in college, so the details of my social education pale in comparison to others like Amy’s. I played Division I hockey, so my weekends were pretty much occupied from October until March. That’s not the reason for my lack of social activity, because most of my teammates enjoyed a “full” social schedule. I loved my four years at Miami University, so I say this with admiration. My four children, two of whom have graduated and two of which are still in school, deserve the highest marks for their social educations. The first two received only average grades for their formal education, but the two in school now, Colton and Piper, have aced both the formal and the social. Take Piper, who last week spent three days on the phone with Amy moaning that she was going to die from flu-like symptoms and was unable to attend classes, but on the fourth day, the day of her boyfriend’s fraternity formal, she was completely cured and was able to attend in full force. I view my kids’ college experiences the way I view the summer Olympics: Tom and Doug received gold medals in the individual social event and silver in the individual education event. However, Colton and Piper are competing in decathlons and are on the path to gold medals.

Copyright © 2022, Second Curve Capital LLC

Copyright notice: This publication is protected by copyright. It is a violation of federal law to reproduce or forward all or part of it to anyone. This includes photocopying, faxing, e-mail forwarding, and Web site posting. The Copyright Act imposes liability of up to $150,000 per issue for infringement.

Printed by:

Copyright 2018, Second Curve Capital, LLC. Copyright notice: It is a violation of federal law to reproduce this newsletter in any way, including via photocopying and email forwarding. The Copyright Act imposes liability of up to $150,000 per issue for infringement.